Poverty effects women the most – fact.

The United Nations’ Millennium Declaration marked a momentous occasion in the struggle for both gender equality and the eradication of poverty; as a key objective, the UN will look to ‘promote gender equality and the empowerment of women as an effective way to combat poverty, hunger, disease and to stimulate development that is truly sustainable’ (UN, 2000).

But what was so special about, yet another, UN objective? This particular goal represented a global consensus on the long-standing link between women and poverty. What was once seen as a here-say common conception suddenly had real, political, weight seen as an undeniable reality. Following such consensus the Sustainable Development Goals have continued the message on this issue (UN, 2016)

Why was this so important to establish?

In this context, the ‘feminisation of poverty’ refers specifically to the notion of women experiencing poverty at a disproportionally high rate in comparison to male counterparts (Abbate, 2010). The prevalence of women below the poverty line is no coincidence, nor is it just an issue just for the women themselves; it must be distinguished in order for it to be addressed and to avoid further perpetuation.

What factors can we hold accountable for such failings?

Although they are not exhaustive, three alternate reasonings have been given prominence in political-literature as to why feminisation is so apparent in poverty (Moghadam, 2005):

Firstly, the continued existence of intra-household inequalities and systematic bias against women and girls. The unequal access opportunities for healthcare, education and nutrition all negatively impact the potential employment and income-generating ability of women; this coupled with the continuing systemic discrimination in households and existing patriarchal structures paint a bleak picture. Continuation exacerbates vulnerability and undoubtedly contributes to the feminisation of poverty (O’Brien & Williams, 2016).

The increase in female-headed families is another long-term cause of poverty. In Western states divorce has become the norm which leaves many women as the sole-provider of the household with no second supplementary-income as in nuclear families. In less-economically developed countries families have this life forced upon them due to conflict or other external factors. The importance of a stable home-life structure on the future development of children is widely acknowledged. Not only does poverty take place most often in these families but the likelihood remains that cycles will continue to rotate as a result.

A considerable amount of research has also taken place focussing on the negative impacts of Neoliberal economic policy. Nagar et al (2002), for example, discussed the way in which the burdens of restructuring policies were bourn by women as a result of their reliance upon unpaid labour. The movement of globalisation has also been mentioned to have adverse effects due to its failure to account for women’s role (Library Index, 2017).

What changes can be made?

At ground-level we, as human-beings, must do our upmost in order to give substance to women’s right for self-fulfilment and determination (Marchand, 2003). In any way that we can we must enable women the genuine opportunities to engage fully in economic and social life without the burden of expectation or presumption.

More importantly, governments must re-think both implemented policies and current-standing institutions in order to value women in all contexts. Buvinic (1998), for example, recommends multiple ways in which progress can be made including: expanding substantially the access of poor women to family-planning and reproductive health services, adopting education reform agendas, building incentives for the private sector to expand women’s access and many more. States simply must take action.

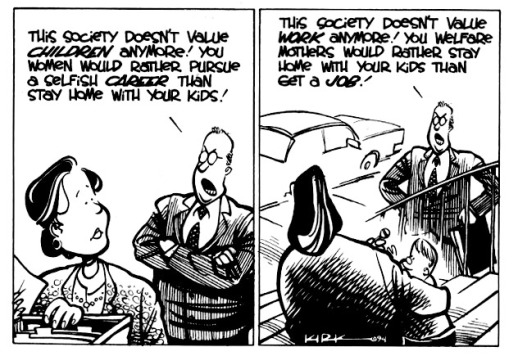

What impact does this have on deeply engrained assumptions on gender?

Fast forward seventeen years from the UN’s 2000 Declaration and one still observes the same issues at hand. Despite historical gains for women in terms of more formal equality (right to be educated, to vote and to own property) there has been a distinct lack of progress towards substantive equality for women (Galloway, 2014).

The older generation are not alone and are also not the last in experiencing feminised poverty. Continuous exposure to such atrocity confines women to second-class status, denying them progressive liberty and perpetuating the standard stereotypes/assumptions made of them.

How can we ever hope to eradicate sexism, let alone poverty, if we are unable to make progress with policy?

Written by Paul Hudson (M00611200)

International Politics, Economics and Law student at Middlesex University.

Sources:

Abbate, L. (2010). Feminized Poverty Worldwide. Available: https://www.mtholyoke.edu/~abbat22l/classweb/feminizationofpoverty/worldwide.html. Last accessed 25th Nov 2017.

Buvinic, M. (1998). Women in Poverty: A New Global Underclass.Available: http://www.onlinewomeninpolitics.org/beijing12/womeninpoverty.pdf. Last accessed 1st Dec 2017.

Galloway, K. (2014). Ending feminised poverty. Available: http://fwsablog.org.uk/2014/10/13/ending-feminised-poverty/. Last accessed 29th Nov 2017

Library Index. (2017). Women and Children in Poverty – The Feminization Of Poverty. Available: https://www.libraryindex.com/pages/2687/Women-Children-in-Poverty-FEMINIZATION-POVERTY.html. Last accessed 5th Dec 2017.

Marchand, M. (2003). ‘Challenging Globalisation: Feminism and Resistance’, Review of International Studies 29 (3). 145-60.

Moghadam, V. M. (2005) ‘The Feminisation of Poverty’ and Women’s Humar Rights, SHS Papers in Women’s Studies / Gender Research 2 (Paris: UNESCO).

Nagar, R et al. (2002). ‘Locating Globalization: Feminist (Re)Readings of the Subject and Spaces of Globalization‘, Economic Geography, 78(3): 57-84

O’Brien, R & Williams, M. (2016). Gender. Global Political Economy: Evolution and Dynamics. 5th ed. London: Palgrave. 210-216.

United Nations. (2000). United Nations Millennium Declaration. Available: http://www.un.org/millennium/declaration/ares552e.htm. Last accessed 25th Nov 2017.

United Nations. (2016). Sustainable Development Goals. Available: http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals.html. Last accessed 12th Dec 2017.